The Belfast Bicycle Network Plan is currently out for consultation. Delighted I opened the pdf. And from there on in my mood wavered between anger, despair and hysterical laughing.

I think these plans are a failure; a failure to capitalise on the momentum for cycling in Belfast; a failure to correct the mistakes in the Alfred Street and Durham Street paths.

It is as if the people who wrote their vision for the network and those who set out the routes never shared a room, let alone a vision.

The plans as presented are a waste of time. I am asking the Department for Infrastructure to withdraw it and think how better to design for those who currently daren’t or can’t cycle.

The document asks 17 questions and I will attempt to answer them.

Question 1: Do you agree that producing a Bicycle network for Belfast is an important element of developing a more bicycle-friendly city? What timeframe do you think it should cover?

The network is crucial in making Belfast more bicycle-friendly. The current infrastructure, or more precisely lack of infrastructure, is a major block to growing the modal share for cycling beyond 5%. The recent growth in cycling has been achieved with next no involvement from government. Very little budget (£1.30 pppa) was allocated and only a few short new cycle tracks were built.

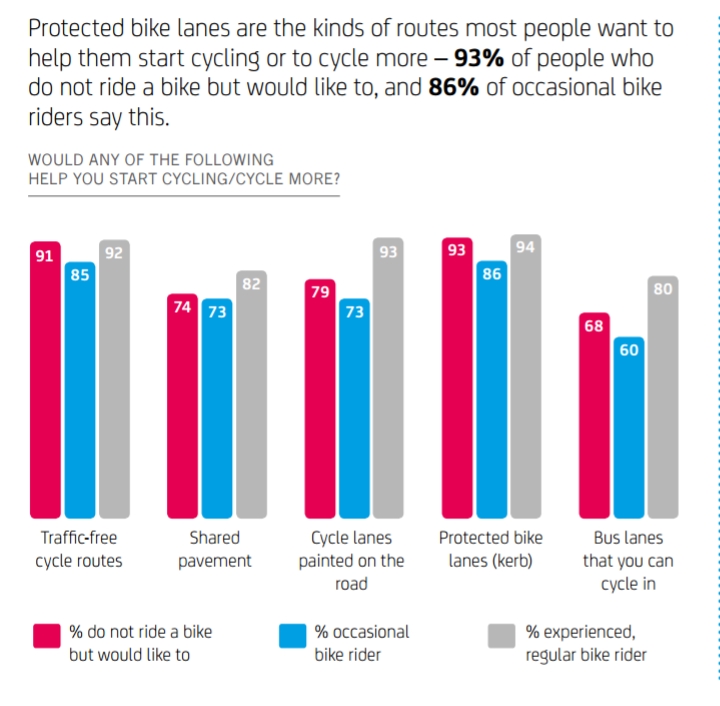

Belfast cyclists remain overly reliant on bus lanes, shared pavement and advisory cycle lanes. Sustrans in their Bike Life survey found that bus lanes were not considered safe or conducive to cycle more.

The perceived feeling of insecurity caused by the proximity of large vehicles is not improved by the decision by the outgoing Minister Chris Hazzard to allow private hire vehicles into the city’s Rapid Transit bus lanes.

The network as set out in this document and amended after the consultation should be built within a 5 year timescale. Some quick wins can be achieved by bringing existing provisions included in the new plan up to highest standards. A 10 year timescale is perhaps required only where large capital schemes are involved, for instance to cross the Lagan at the Gasworks.

A brake on developing cycling in Belfast

Adoption of this strategy in its current form would push the building of highly necessary paths along arterial roads beyond a 10 year timeframe. This will put a brake on development of cycling in Belfast.

It has to be noted Rotterdam (admittedly from a much better starting position) has set itself a 2 year target on delivering a much improved network of paths. Their plan includes improving accessibility across the city core, improving bicycle traffic flow and making safe numerous paths and junctions.

This strategy must be delivered in a 2 to 5 year timeframe.

Question 2: Do you agree that these five criteria from the BMTP are still valid for the development of a network for Belfast? If not, what do you consider the criteria should be? Please explain.

Yes. But.

Like many estates planned in the latter half of the 20th Century Rathcoole Estate in Newtownabbey is blessed with a considerable network of off-road paths. Most of these are designated footways. These footways are used by cyclists as a safe alternative to a hostile car-centred road environment.

A major nearby destination is the Abbeycentre shopping complex. It can be reached on foot or by bike using the network of paths without having to use any major roads.

A number of links exist to the NCN Shore path. With better signposting and fixing crossings on the A2 Shore Road a cyclist can travel from their home in Rathcoole to their employer’s in the Harbour, City Centre or beyond without needing to share with cars on main roads.

The local network of paths and the way it connects to destinations should be inspiration for the bicycle network across Belfast. It should give door-to-door opportunities for active travel, an alternative to going by car.

But what about the children?

In the Netherlands most children cycle to school, preparing for a continuation of a healthy life choice into adult life. They can because infrastructure enables them to cycle, often unaccompanied, without safety concerns.

Similarly, libraries, hospitals and health centres should be easily accessible by a network path, enabling service users of all ages access to vital community services.

NIGreenways has already pointed out the poor overlap between the planned network paths and location of schools. The proportion of children cycling to school is firmly stuck at 0%. This is a scandal, and should be top of politicians’ agendas.

The planned network doesn’t just miss out schools, it also does not allow direct access to major destinations in the Greater Belfast area. For instance, there is no planned direct link between the new Transport Hub to the Royal Victoria Hospital along Grosvenor Road, instead preferring a detour along the noisy, polluted and people-hostile Westlink.

Similarly, cyclists from southwest Belfast and Lisburn will face lengthy detours to reach the Belfast City Hospital or the Queen’s University campus using network paths. The plans from the outset sacrifice the core principle of directness.

The city’s local shopping areas are poorly served by the network. Bicycle lanes have been shown to boost business where they have been installed. It is difficult to see how the network in its proposed form will generate economic benefit for Belfast traders.

Arterial routes

What are missing, glaringly, are paths that run along arterial routes, where many Belfast retailers and businesses are found.

Currently, Belfast is groaning under the weight of congestion. Belfast’s Lisburn Road is said to be the most congested road in the UK, outside London, in the evening rush hour. Similarly, Ormeau Road is most congested in the morning.

Previously I set out a few ideas of what can be done on the Lisburn Road to reduce congestion. The Department for Infrastructure introduced the 3-five-10 strategy to enable more to walk, cycle and use public transport. Cycling will not be a credible alternative to car users on the Malone Road or Lisburn Road if the nearest network paths are the Lagan Towpath or along Boucher Road over half a mile away.

It is my opinion that a designated cycleway with priority over side roads running along the Lisburn Road from central Belfast to Lisburn town centre will offer people a choice to leave the car at home.

Combine it with meaningful numbers of secure bicycle storage areas at railway halts and principal bus stops will enable people to use various modes for their journeys.

Other arterial routes will also benefit from having high quality designated cycle paths alongside.

It is laudable that a large proportion of Belfast households are designed to be within 400m of a network path. Except that many homes nearby the network do not have easy access.

Accessibility

The map is very simplistic and appears to count number of households within 400m of a path. Consider the Comber Greenway. It is built along the old Belfast and Co. Down railway line. It has few access points. The railway line was not meant to interact with local streets much. Properties in, for instance, King’s Park Lane back onto the line, but to access it residents must walk or cycle 640m to the entrance beside Knock police headquarters.

Similarly, residents in Edenderry at the very southern edge of Belfast, can see the Lagan Towpath from their front step, literally a stone’s throw. But to access it directly with anything other than a lightweight bike is practically impossible due to the stepped bridge across the Lagan and narrow chicane of fencing at the village entrance. It is a 1.2km ride to the next nearest accessible entrance at Shaw’s Bridge.

It would better to count the households within 400m of an access point that enables bicycle users of all ages and abilities to use the network, and it is my guess that suddenly the map doesn’t look so good.

Question 3: Do you agree that the development of a Belfast Bicycle network is a key element in giving those who would like to cycle (but currently don’t) the freedom and confidence to do so?

Yes. The Belfast Bicycle network, if built and maintained to high standard and not compromised to accommodate pedestrians, mopeds and motorcycles, cars, taxis or buses, will provide an environment where those who currently don’t cycle to go out without worry about their personal safety.

Question 4: Do you agree that the objectives in 3.9 should be applied to the network? If not, what objectives do you think should be set?

Here are those objectives:

Firstly, it is good that the objectives concentrate on commuters, amenity and leisure cyclists. We currently see on Belfast roads hard core year round commuters and lycra clad racers. Amenity cyclists are poorly catered for.

There is no specific mention of age and ability in the objectives. It needs to be clear that the network will be designed to guarantee the safety of children cycling unaccompanied to school and those in the latter stages of life, vulnerable to falls, out for a leisurely ride on an e-bike.

The network should be accessible and near to all people within Belfast; to people of all ages and abilities, those who currently cycle those who currently daren’t or can’t.

For amenity cyclists it is necessary the network goes near amenities, such as shops, schools, libraries and health centres. If the path leaves you far from your intended destination is it of any use? It would be good to see the map of routes redrawn to include as many shops, schools, libraries, leisure centres, hospitals and health centres as possible.

Consistent high quality provision

What makes cycling in the Netherlands such a pleasure is that the network of paths is of high standard throughout large parts of the country. This standard follows guidelines and design principles set out in the Fietsberaad CROW manual. Vigorously applying the same high standard throughout the Belfast network should ensure cyclists are not left to fend for themselves on 60mph dual carriageways, roundabouts and junctions.

Quietways

In London Quietways have been set out, apparently without much regard for existing traffic volume or taking measures to reduce traffic volume along the route. It leaves bicycle users navigating their way through streets busy with HGVs and along ratruns.

Modal filtering, keeping certain vehicle types out of streets where cyclists have priority, must be included to reduce traffic volume and speed in order to make Quietways work.

Repeating mistakes

In Hackney streets have been made calm and more liveable through permeable filtering. Walking and cycling in becalmed areas is a joy. Where Hackney fails, and fails badly, is ensuring cyclists’ safety along main traffic corridors. There have been fatalities especially along main roads. Hackney also has a worrying high level of hit and runs.

Bicycle users, of any kind, are choosing main roads over back streets because they want to traverse an area rapidly to get to their destination, or need to visit amenities along the main road.

This network plan leaves Belfast in danger of repeating London and Hackney’s mistakes. It potentially sends cyclists down ratruns, along roads where cars dominate and where they are offered little protection.

Another mistake is the use of coloured paint to mark cycle provision. In London slippery paint has been implicated in the death of a motorcyclist and numerous less serious falls. In the Netherlands coloured tarmac is used:

The use of the words encourage and promote grates. If the network is consistently of high standard, accessible and attractive to use, encouragement and promotion is superfluous. Make the network a better and cheaper alternative to car use and people will start using it.

Question 5: Do you agree that the primary network should be based on the concept of arterial and orbital routes?

Yes. But.

Not the arterial routes set out in the plan, but instead following the main traffic or Metro corridors in the city. With modification the network of routes as set out in this document can act as a secondary network reaching into the heart of neighbourhoods.

Last resort

Many of the proposed routes follow the Community Greenway footpaths set out in the Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan (2015). Considerable adaptation and financial commitment is needed to make these Community Greenway routes usable for cyclists. And shared use paths, such as Community Greenways should be a last resort, when no designated space for cycling can be safely fitted in along main arterial roads.

Belfast bicycle users on the route of the proposed Community Greenway between Shaw’s Bridge and Whiterock

Question 6: Do you agree that the network should be developed in Primary and Secondary stages as outlined in 3.13? If not, how should it be developed?

Here are those two stages:

No. Developing the network in this way is fundamentally wrong. The level of separation should be decided by size, speed and volume of traffic a road is carrying. And in turn the size, speed and volume of traffic is decided by the primary function of a road or street.

Trunk roads

So, Belfast’s A55 ring road, a busy trunk route, should ideally have fully separated bidirectional cycle paths on both sides with grade separated crossings, so ensuring a minimal number of areas of conflict. The current provision is a long way off from this ideal.

Above is a trunk road, the N273, just south of Venlo in the Netherlands. Having bidirectional paths either side allows cyclists to get to their destination without having to cross the main road. The number of crossing points can be kept to a minimum.

Local access

At the other end of the scale, streets that only serve as access to properties can, with traffic calming and a 20mph speed limit enforced by road design make do without any segregation for cycling.

In the picture above through traffic is kept to the main road in the background. A bidirectional cycle path leads cyclists safely underneath the provincial road. The path connects to the city centre and a cycle superhighway. The street in the foreground only allows motorised vehicles access to adjacent properties and has a 30 km/h (20mph) limit.

Distributor roads

On these distributor roads designated cycle space is needed, due to traffic volume, traffic speed and presence of HGV.

Distributor roads allow joining up of local access streets and main trunk roads. They are busier than access roads and are often lined with businesses. They are not meant to carry traffic originating outside the area going to a destination somewhere else outside the area.

Confusion and delay

In Belfast these road functions are blurred. Distributor roads act as thoroughfares for regional traffic and vice versa. Worse, across the city quiet residential streets, access streets, are used by commuters to avoid certain junctions. These access streets then take on the role of a distributor or even a trunk road.

This blurring of functions, mixing traffic users with differing intentions is one of the root causes congestion. It is better to disentangle these functions and so allow for more homogenous traffic flow.

The primary function of a road, the dimensions, speed and volume of traffic must dictate the level of segregation needed.

Question 7: Do you agree that we should consider requirements of likely users on a scheme by scheme basis, for example routes which will primarily be used by children on the school journey may be best served as shared track?

No, design it right

The entire scheme should offer users an expected level of quality throughout. Dutch experience shows commuters, schoolchildren and leisure cyclists of all ages and abilities can and do use the same paths to reach their destination. And people on roller blades, powerchairs, mobility scooters, etc:

We don’t offer bespoke roads for certain groups of car drivers. Whether they are business users, commuters, shoppers or going out for a trip to the seaside they all use the same network and expect the same standard of provision throughout.

Singling out a certain user group and making the cycle provision meet their specific requirements puts other cycling groups at a disadvantage.

St. Bride’s Primary School sits in between two major roads in South Belfast. Children from the surrounding area could cycle to school were a safe designated space for cycling provided. The two roads are also very popular with commuters to the nearby Queen’s University campus and Belfast City Hospital. Whose needs prevail?

The answer is, of course, to design it right and children, commuters, leisure cyclists can all use the same designated bicycle space.

Again, shared tracks should only be used as a last resort as they are inherently compromised to suit the divergent demands of different groups of road users.

Question 8: Are there any other kinds of bicycle infrastructure that should be considered? What are they? Do you have any views on which types of infrastructure, if any, should be favoured in developing a network for Belfast?

The document sets out how the Department will provide for cycling between junctions. It does not set out how cyclists will get across junctions.

Firstly, any network path should clear priority over traffic on minor streets crossing it. This can be reinforced by making path and the footway beside it continuous.

A bus stop bypass is visible in the background. These should be included on all routes where they pass a bus stop.

At junctions the path should should be set back from the main thoroughfare so that a turning vehicle can wait for cyclists to pass without obstructing the flow of traffic.

Currently, where there is provision, it ends before the cyclist gets to a junction or roundabout. At the junction or roundabout cyclists left to fend for themselves. Even on new infrastructure such as the Durham St path, the issue of junctions has been fudged with areas of shared space and strange transition arrangements.

The Department needs to start providing junctions and roundabouts with in-built protection for cyclists. Belfast City Council, in their response to the Bicycle Strategy, wish to see Dutch roundabouts.

Missing from the plans are grade separated crossings across trunk roads. The plans feature reopening the tunnel on the Abbey Road (an access street) on the Comber Greenway, but do nothing at all on the A55 crossing beside Knock Police HQ.

At Broadway roundabout, a major hub for the planned routes, cyclists are forced to make use of 4, sometimes 5 separate button-controlled crossings.

For such busy junctions grade separated crossings for pedestrians and cyclists would be best.

The roundabout’s design team however did not consider people cycling at all. They did not foresee a Belfast Bikes docking station being installed. They did not think cycling could become more important in Belfast. Now it’s built it is hard to see how cycling can be given a safe designated space without major investment.

Cyclists are left with poor infrastructure.

At Tillysburn there is an opportunity to do something great to replace the current glass-strewn bear pit.

Hovenring, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Hovenring, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Question 9: Do you support the use of the network requirements as detailed at paragraph 5.1?

Yes.

At every stage from planning to implementation to review the guiding principles of the network must remain central and constant. As our city and traffic evolves, so the network must evolve to meet user demand or deal with the challenge of, for instance, autonomous vehicles. The core principles should not be compromised or degraded as the network is built.

Sadly, the Alfred Street path shows how in the period between design and completion these guiding principles were compromised, allowing motor vehicles to slip between wands and block the lane and not offering enough protection at junctions.

Question 10: Do you agree with the addition of ‘Adaptability’ as a network requirement? What other requirements would you like to see included?

Question 11: Do you agree that the routes should be planned and facilities designed with the achievement of increasing numbers of people cycling in mind?

I’ll answer these as one question.

Obviously, the network will need to built to accommodate the target volume of cycle traffic. The Bicycle Strategy sets a target of 20% of journeys under 1 mile and 10% of journeys between 1 and 2 miles for cycling.

How Rotterdammers get around (Bike Portland)

The targets set for Belfast are puzzling. The share for cycling in Rotterdam peaks at around 3 miles. Belfast’s cycling supposedly peaks below 2 miles. How does this sit with the NI Travel Survey?

Cycling doesn’t register against walking and driving in Northern Ireland. Digging deeper into data reveals the peak of cycling journeys lies between 2 and 5 miles.

And the average journey length is 5.1 miles.

Humans in Rotterdam are not vastly different from those in Northern Ireland. Humans tire and for most walking more than 2 miles, or cycling more than 5 miles requires too much effort.

The network should not be built for the current 0-5% of people who use bicycles regularly and then adapted to accommodate a greater number in 5 or 10 years time. It should be built to accommodate the target of 20% share from the outset.

Look at how the cycling provision at Broadway roundabout has become set in concrete, with little room to grow cycling numbers on the far from adequate shared use space.

If adaptability is adopted as a core principle it should be so that cycling can grow and not be constrained by keeping the current state where cars utterly dominate Belfast streets. This requires new thinking at Department for Infrastructure, who thus far, even in writing this consultation document, are reluctant to remove road space from cars and redesignate as cycling space.

Question 12: What are your views on segregation between people who walk, people who cycle and people who drive? What are your views about physical segregation between motorised traffic and non-motorised traffic? Do you agree that there are levels of traffic (footway or carriageway) below which physical segregation is not always necessary – such as quiet routes and residential areas?

Sustainable Safety

The underpinning thought of designing roads should be sustainable safety, so that an error by a road user will not have fatal consequences for themselves or others.

The second principle is hierarchy of control: where there is a risk, eliminate it; if it cannot be eliminated manage it (in descending order of effectiveness) by substitution, design, laws and education and if after all that a risk remains use personal protective equipment.

On roads the risk of fatal and serious road traffic collisions is reduced by removing areas where cyclists and cars use the same space. Along busy roads and roads where traffic speed is 30mph or above and environments where there are more than average numbers of HGV separation is needed. This is not optional, it is a must to increase cycling numbers.

If Belfast eyes a target of 20% share for cycling it will need to consider how this has an impact on current shared use provision. How will the crossing of the Lagan Towpath with the Ormeau Road look with 4-6 times the number of cyclists?

An underpass will only partly reduce congestion at this point as many, if not most, cyclists use the footpath to cross the bridge.

One Path to conflict

Already, there are numerous incidents along the Towpath and Comber Greenway. To reduce these Sustrans have introduced the One Path initiative to share the paths. Or to put it in other words: on shared use paths we are already in trouble when cycling has an overall modal share of 3-5%. What will this be like if cycling achieves a 4-fold increase?

Hierarchy of control dictates that an education exercise won’t be very effective and separating cyclists and pedestrians will work better to avoid conflict.

Below is a picture of the Ruhr Cycle Superhighway being built near Mülheim in Germany. It shows clear separation between the pedestrian path on the right and the smooth wide tarmac for cyclists on the left.

As shown before, on quiet residential streets there is no need for separation, provided traffic speed is 20mph or below and traffic volume is low. The best way to achieve good conditions for 8-80 cycling is to consistently stop ratrunning and designing roads to self-enforce a 20mph speed limit.

Again, calming traffic by road design and clarifying an access street’s purpose by removing ratrunning vehicles is not optional, it’s a necessity to enable 8-80 cycling.

Question 13: How important is the requirement that ‘routes need to flow’? What kind of signage should be provided? What facilities should be provided?

The paths should be easily recognisable as cycle paths to stop drivers erring into them. And cyclists will more easily follow a clearly set out trail. This is best done by using coloured tarmac.

Wayfinding has to be simple and straightforward with dedicated clearly legible signage. Different routes could have their own colour or theme to improve recognition.

Tourists will use these paths so signage should be simple to understand to non-English speakers, perhaps showing amenities as pictograms rather than words.

Additional facilities: increase number of cycle racks along routes, especially near shops, libraries and health centres. The plans recognise the paucity of secure bike racks in Belfast. Bicycle hangars could be placed in inner city neighbourhoods to enable people to securely store their bicycles when their homes have no available cycle storage space. Already mentioned are secure bike lock-ups at bus route termini principal bus stops and railway halts.

Public bicycle pumps and bicycle repair tools could be placed at various locations for those who need to carry out a quick roadside repair.

Bicycle counters must be placed at a number of locations to show that the paths are being used and numbers of cyclists are growing.

Question 14: What is the relative importance between construction of a route and its maintenance? What other guiding principles would you suggest? Please explain.

This is not a question. The built network needs to be maintained. Lights need to work, rain must not cause flooding. Clearing snow and gritting when it’s frosty should be done to prevent falls and enable year round cycling.

Question 15: With reference to the appendices please set out your views on the proposed routes. We are interested in the positives or negatives associated with the various sections of the proposed routes.

Question 16: What are the specific issues that may arise if bicycle infrastructure was constructed along the proposed route?

Question 17: What other alternative routes are available?

With so many fundamental errors in these plans it would seem nitpicking to lift out pros and cons within each scheme. However, they asked the question:

The main positive points:

- Provided the segregation is up to highest standard and junctions and roundabout offer protection to cyclists a path along Boucher Road connecting the Lisburn Road at Balmoral and the Royal Victoria Hospitals will be of great benefit to staff and service users of the Royal, but also allow better access to the Boucher retail area, home to two bicycle shops.

- The proposed Route 1 between Holywood and Holywood Exchange to central Belfast will give commuters from Holywood an alternative to the car, but also allow leisure cycling from Belfast to Bangor along the North Down Coastal Path.

- The A55 route will knit together the current paths of varying standard.

Even as you start summing up the positives the negatives come crowding to the fore:

- The near total disregard of main arterial routes, lack of directness and poor connections between residential areas and amenities. Designing for failure.

- The reliance on sharing space with pedestrians on almost every proposed route. Designing for conflict.

- The lack of grade separated crossings across Belfast’s Outer Ring. Designing for death.

What do these routes look like in winter, after 7pm, or before dawn? Many routes pass through gates which are shut as early as 4:30pm. Are path users to be abandoned, with literally nowhere to go?

And you do wonder at what stage of the night and however many cups of coffee it seemed like a good idea to send cyclists up a road with an 19% incline:

Great post. Great blog. Great plan. Cycling is the fastest way of getting from A to B over shortish distances without having to drive. It’s usually faster than driving, by the time you’ve sat in traffic and found parking. And if the routes were safer and more direct, more people would cycle. It seems so simple and so obvious, but the planners don’t seem to get it. It’s very strange.